The rapid growth of online advertising hides a serious challenge: the digital world has developed faster than the tools needed to measure it. This problem has made it difficult for marketers to fully exploit the Web’s promise as the most targetable and measurable medium in the history of marketing. Can digital advertising live up to its potential?

The rapid growth of online advertising hides a serious challenge: the digital world has developed faster than the tools needed to measure it. This problem has made it difficult for marketers to fully exploit the Web’s promise as the most targetable and measurable medium in the history of marketing. Can digital advertising live up to its potential?

It’s going to take some time. A June 2008 McKinsey digital-advertising survey of 340 senior marketing executives1 around the world shows the breadth of the gap between what’s needed and what’s available. Hobbled by nascent technologies, inconsistent metrics, and a reliance on outdated media models, marketers are failing to tap the digital world’s full power. Unless this problem is addressed, the inability to make accurate measurements of digital advertising’s effectiveness across channels and consumer touch points will continue to promote the misallocation of media budgets and to impede the industry’s growth.

Some companies, though, are making progress. The most exciting innovations are taking place in three areas. In media planning, marketers have been developing analytics that allow them to compare the effectiveness of on- and offline efforts. They are also developing a better appreciation of how online marketing messages convert shoppers into buyers, both online and in stores, and using these insights to make specific digital-advertising techniques more effective. Third, to target advertising messages with greater precision, a few leaders are learning to measure the ties among people in social networks—something we call the optimization of social media.

The measurement challenge

Digital advertising has grown strongly over the past six years. Ninety-one percent of the marketing executives in our survey say that their companies are advertising online. Many are beginning to experiment with emerging Web 2.0 vehicles, including widgets, wikis, and social networks. Over half of those surveyed indicate that their companies plan to maintain this spending at current levels or even to increase it where possible. Respondents whose companies are introducing rigorous measurement techniques report a higher level of satisfaction with digital marketing. In fact, 55 percent of them are cutting their expenditures on traditional media in order to increase funding for their online efforts, compared with only 43 percent of the respondents whose companies don’t measure the impact.

These numbers make it all the more surprising that companies have failed to crack the code for measurement. Indeed, a comparison of our 2007 and 2008 surveys suggests that most companies have made little progress in this area. Only a minority of advertisers use quantitative analytical techniques to optimize online marketing. In response to a question about how budgets are allocated across different media, 80 percent of the respondents say that their companies either use qualitative measures—that is, subjective judgments—or simply repeat what they did last year. Over half say that they are not satisfied with the current process of allocation and measurement. The most frequently cited barrier to shifting more money online is “insufficient metrics to measure impact.”

Even if measurement is relatively straightforward, marketers are apt to use a qualitative rather than quantitative approach. When we asked respondents how they gauge the effectiveness of their digital-brand-building efforts and direct-response advertising, their answers revealed a startling failure to measure. Only half of the respondents’ companies use even the most basic of metrics—the click-through rate—to evaluate the impact of direct-response advertising. Similarly, only 52 percent of the respondents whose companies are trying to build their brands assess the increase in brand strength.

The numbers drop even further when we asked respondents about more sophisticated techniques. Most companies recognize that their customers’ purchasing decisions result from a number of contact points. A single purchase, whether online or in a store, might be influenced by any combination of, say, the comments of a friend, information on a Web site, a recommendation from Amazon.com, a store visit, or contact with a call center. Yet only 30 percent of the marketers in our survey report that they consider the offline impact of online marketing. Marketers who do look at those metrics are generally more satisfied with their online efforts: they planned to increase spending on it by 38 percent, compared with 26 percent for those who didn’t conduct that analysis.

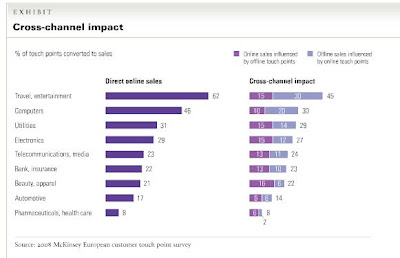

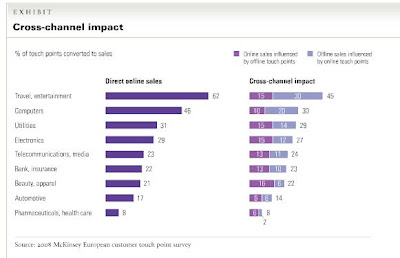

Poor measurement can have an impact more severe than just a few lost return-on-investment (ROI) percentage points; it can inspire fundamentally bad decisions. In late 2007, for example, McKinsey conducted a study of 3,000 European broadband users. This study, which followed an earlier one in Belgium, showed that consumers are increasingly apt to combine online research with offline purchasing and vice versa. In fact, purchases made strictly through a single channel make up less than a third of the total. Any company that measured a site’s effectiveness solely through online sales would miss much of the impact and therefore risk underinvesting.

Just as important, many marketers fail to measure the ability of offline media to influence online sales—another omission that could lead to misallocations. The European broadband study showed that 60 percent of online purchases involve an offline touch point, either at the brand-awareness level (“I know this brand from a TV commercial”) or at the consideration level (“I browsed through a magazine and noticed an ad that referred to a Web site”). A US home-furnishings retailer found recently that almost a quarter of its online buyers use its stores to investigate products before making a purchase. In fact, almost half of the retailer’s shoppers reported that it was critical for them to examine products in a physical store before purchasing online. Without this insight, management might well have underestimated the value of stores in driving online revenues. The European study found that, in many areas,2 offline sales driven solely by online activity plus online sales driven by offline activity together represented an amount more or less equal to total online sales (exhibit). Thus, marketers who fail to assess the cross-channel impact of their advertising underestimate its effectiveness dramatically.

Emerging solutions

There are some signs of progress in efforts to measure the effectiveness of online advertising, even across channels. Although a majority of companies still have a long way to go, some marketers have made rigorous measurement a priority. As one participant stated in a recent McKinsey online discussion among marketers using sophisticated analytics: “If we can’t measure it, essentially, we don’t do it.”

As for allocating ad budgets, leading marketers are now using metrics that permit comparisons between offline and digital spending. One marketer—a home-furnishings rent-to-own chain—used a method called RCQ (for reach, cost, and quality) to optimize its allocation of spending among ad vehicles. This metric, combining rigorous analytics with systematically applied judgment, measures the number of people each ad vehicle reaches and the cost of reaching them by vehicle. It also includes a quality factor based on changes in engagement, attitudes, and behavior. The RCQ analysis showed that the chain spent too much on its workhorse vehicles, such as direct mail, and too little on television infomercials (which convey more information) and online ads (which can be targeted more precisely).

Some participants in a recent McKinsey online discussion among marketers say they were moving in a similar direction. “While the ROI–ROE may be a little ‘apples and oranges’ for some channels,” one participant said, “we create generic key performance indicators across most of our efforts and compare the effectiveness of each channel.”

Some retailers and automotive companies are trying out quantitative ways of assessing the impact of on- and offline ads in other sales channels. One specialty retailer, for instance, tested the effectiveness of online vehicles such as banners, affiliate programs, and paid search in driving sales both online and offline. The retailer used coupons redeemable on its Web site and in stores to track results across channels. The test showed that online media vehicles promoted offline sales very effectively: more than three-quarters of the coupons were redeemed in stores. This finding led the retailer to shift its spending away from some traditional media, particularly newspaper circulars, to online vehicles. The ability to track the impact of all spending across channels continuously might be a few years away, but the payoff is already clear.

Techniques for optimizing online ads have come even further. “Programs and interactions are constantly changed, based upon measurement,” said one participant in the online discussion. “This may even include real-time changes in interaction, based upon different control tests. We change format, site selection, network structures, and buys.” Some marketers are starting to use the technology that manages online ad campaigns (the ad-serving platform) to assess the impact of all online touch points, instead of basing the optimization of media on the last click before a conversion. (More often than not, that is a branded paid-search term.) This approach requires an understanding of response rates by customer segment in order to serve more relevant ads across third-party sites and a marketer’s own site.

Finally, companies are starting to tap into the real promise of social media. Our research showed that a major European cable company undertook a marketing campaign along these lines to sign up customers for a cable service. The campaign, targeting online customer segments, sought to maximize the ROI of each individual ad opportunity by serving whatever ad most promisingly combined likelihood to convert with profitability of conversion. After the company segmented its customers by the sites they visited online, it could use each person’s past behavior to deploy the most appropriate ad vehicle—e-mail, graphics-rich media, or video. This strategy raised conversion rates by 50 percent.

McKinsey research on telephone users’ social networks suggests that even they can be measured to allocate marketing budgets more successfully. One telecom company, for example, has learned how to retain phone customers by assessing the strength of the relationships among them. The company used call patterns, changes in call volumes, types of payment (prepaid or contract), handset types, and other traits to identify customers likely to leave for another carrier. Meanwhile, it constructed a diagram of their social ties, derived from the people they called, the people those people called, and how often. In general, the more closely anyone was tied to someone who unsubscribed, the more likely that person was to unsubscribe in turn. In this way, the telecom company improved its churn prediction model by 50 percent. Moreover, by identifying the most influential potential churners and working to retain them with new services and price plans, the company not only retained a quarter of them but also reduced the churn rate within their social networks by almost 40 percent.

Another telecom company used a similar social-network mapping technique, based on the e-mail traffic of customers who also subscribed to a broadband connection. On the theory that members of a network have similar needs, the company offered people in its customers’ e-mail networks the same telephone and broadband plans its customers had. The campaign had a conversion rate that was up to 80 percent better than that of other direct-marketing campaigns we researched.

Online media have enjoyed tremendous growth and will continue to do so. Our survey suggests, however, that this growth will be far more robust if marketers implement accurate measurement techniques that help them understand the true impact of ads.

Source -

McKinsey Quarterly